August 24th, 2016

The first 25 miles south of Cali follow the flat and easy bottom land of the Cauca Valley to its southern terminus at Santander. After that the terrain becomes mountainous. The city of Popayán lies at over 5000 feet, only 2000 above Cali, but a merciless 50 miles of up and down to get there. This was only the beginning. Getting to Quito would see me going from low points of 3 and 4000 ft, descending once to nearly a 1000 feet, up to as high as 10,500 feet a total of 6 times before reaching Quito, Ecuador. The pitiless hills would drop to arid, desert climate, with prickly pear and pitaya cactus, then climb, over sometimes two-day rides, to genuinely cold and rainy summits in páramo habitat.

The highway to Popayán from Santander is lined with houses and small farms built long ago in a manner that could not have foreseen the modern world’s overwhelming amount of truck, automobile and motorcycle traffic. The noise I can see locals getting used to, but living with the terrible air along the crowded highway would not be enviable. On the bike, pollution from immediate traffic has been a problem off and on since leaving the U.S. where our emission standards really make a positive difference. Many of the motorcycle riders here, which at least equal the number of cars, wear respirators. It’s not always that bad, but I’m considering getting a respirator to have when it is. La Linea (see previous post) was the worst.

Motorcycle transportation throughout Latin America is popular and the methods of hauling stuff hilarious. They’re typically not big bikes, in the 125cc-175cc range, and what we would have called “enduros” way back when. I could never have the camera ready when the time was right, but some of the funnier ones have been: A family of four- mom, dad, juvenile and infant all loaded on; grandson giving grandmother a ride with grandmother riding sidesaddle and not looking especially happy about things; rider with passenger reaching his arms behind and toating a wheel barrow filled with cargo and going a good 30 mph; rider with passenger carrying a load of PVC pipe in 15 foot lengths over their shoulders; young couple with a medium sized dog squeezed between them; motorcycles pulling pickup-sized trailers, one I remember loaded to about eight feet high; good motorcycle towing broken down motorcycle; one motorcycle cop off his bike so he could push-start a second motorcycle cop (only in Guatemala).

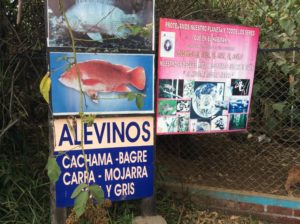

At the town of Tunia, nearing Popayán, I encountered more protests, this time a group called Asoinca had blocked traffic. Cars, motorcycles and trucks were lined up for a couple of miles. This was more of a one-day affair and cops appeared to be there more as a perfunctory presence. People were all smiles. They weren’t letting bicycles through, however; so I was stuck for over an hour until I finally reconnoitered a way passed. I had lunch on some shady roadside grass and while I was eating a nearby property owner came over and introduced himself. He turned out to be a limnologist from Naples, Italy. He spoke enough English that we could communicate pretty well but I never got the whole story of how he ended up in this out-of-the-way corner of Colombia doing some sort of independent work with fresh-water fish. He was shaking his head at the protesters saying that this was more of a social gathering of middle-upper-class leftists who might be called drugstore revolutionaries by an Americano.

I found a way through the protesters and subsequent line of cars and trucks coming the other way. I got several miles of traffic-free travel till another major road intersected. I made it to Popayán and scrambled for Wi-Fi to send in some answers to an email interview for an article about the trip for my hometown newspaper in Logan, Utah. That took till after dark and I ended up in a somewhat spendy, but very nice, hotel in Popayán.

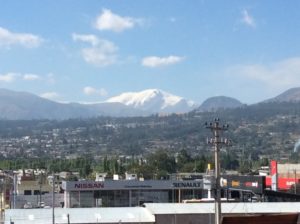

After Popayán a long grade and descent took me to the 1000 foot low point. Two days climb from there got me to Pasto, named after an indigenous culture, and a picturesque city at 8300 feet. Pasto lies at the foot of the active volcano, Volcán Galeras, which erupted as recently as 1993 and killed six scientists who were descending into the crater to collect gas samples. From Pasto, continued grade leads over a 10,000 foot pass then down again to about 4000 feet, then up to Ipiales and the border with Ecuador. From Ecuador’s border town of Tulcán you climb to 10,500 feet, then down to about 5000, then up to 7300 and the town of Ibarra. From Ibarra, where I spent two days in a decent $10-a-night hotel recouping, you continue a climb to 10,000 again, then back down to about 6,000, then up to the final 9,400 at Quito. If your having a hard time following all this, don’t worry, so am I- the innumerable hills have become a blur and there’s more to come. They’ve been unbelievably long and my knees could use one more gear to down-shift into. To endure them you fall into a sort of meditation where your putting the minimum effort possible to just keep the bike in motion while trying to let your mind wander to where ever it can to pass the time. I write the blog, practice Spanish, plan what I need in the next town, get mad at the last bus that cut it way closer than he had to. It’s all about patience, but though time may pass slowly, it’s not boring. Going through the vegetation transitions is always interesting and with hills comes views. In the clear skies here, which contrast remarkably with the smokey skies of Mexico and thick, sea level air of Central America, the views are incredible. Getting to the top of anything is always satisfying.

I stopped in the town of Otavala, 20 miles beyond Ibarra, looking for a grocery store. They had a Saturday bazar going that filled the streets for several blocks in all directions. Of the many that sold clothing, I noticed for the first time since leaving the US “pile” jackets that are worn by climbers and folks in colder climates. I bought a jacket, pile pants and longjohns at DI prices.

I’m in Quito now for a couple of days tracking down bike parts (never simple) and a stove for the one I lost with the pannier in Mazatlán. The luxury of a stove I didn’t miss in tropical jungle habitat where hot food just wasn’t attractive, but I’ll now be at higher elevations for a good part of the next few months and it would be nice to heat water for morning coffee and cooking dinner. Jonathan, from Otavalo, directed me to Quito’s yuppie enclave, Foch’s Plaza, where those types of things are sold along with having a Champs Elysees of coffee shops and restaurants. I’m enjoying the place, but parting with a bunch of money in the process. I have a backlog of flower photos that I’ll put out in another plant segment at some point.

For all the coffee lovers I’ll leave you with info from Fernando Mendivil (and Alfredo Islas) of Los Alamos Cafe (“The Poplars”) for some of what goes into processing coffee beans. These guys are totally committed to the world of COFFEE and brew it as well as I’ve seen the entire trip. If you get to Navojoa, Mexico (Sonora) stop in!

WET PROCESS

In the wet process, the fruit covering the seeds/beans is removed before they are dried. Coffee processed by the wet method is called wet processed or washed coffee. The wet method requires the use of specific equipment and substantial quantities of water.

The coffee cherries are sorted by immersion in water. Bad or unripe fruit will float and the good ripe fruit will sink. The skin of the cherry and some of the pulp is removed by pressing the fruit by machine in water through a screen. The bean will still have a significant amount of the pulp clinging to it that needs to be removed. This is done either by the classic ferment-and-wash method or a newer procedure variously called machine-assisted wet processing, aquapulping or mechanical demucilaging:

In the ferment-and-wash method of wet processing, the remainder of the pulp is removed by breaking down the cellulose by fermenting the beans with microbes and then washing them with large amounts of water. Fermentation can be done with extra water or, in “Dry Fermentation”, in the fruit’s own juices only.

The fermentation process has to be carefully monitored to ensure that the coffee doesn’t acquire undesirable, sour flavors. For most coffees, mucilage removal through fermentation takes between 24 and 36 hours, depending on the temperature, thickness of the mucilage layer, and concentration of the enzymes. The end of the fermentation is assessed by feel, as the parchment surrounding the beans loses its slimy texture and acquires a rougher “pebbly” feel. When the fermentation is complete, the coffee is thoroughly washed with clean water in tanks or in special washing machines.[4]

In machine-assisted wet processing, fermentation is not used to separate the bean from the remainder of the pulp; rather, this is done through mechanical scrubbing. This process can cut down on water use and pollution since ferment and wash water stinks. In addition, removing mucilage by machine is easier and more predictable than removing it by fermenting and washing. However, by eliminating the fermentation step and prematurely separating fruit and bean, mechanical demucilaging can remove an important tool that mill operators have of influencing coffee flavor. Furthermore, the ecological criticism of the ferment-and-wash method increasingly has become moot, since a combination of low-water equipment plus settling tanks allows conscientious mill operators to carry out fermentation with limited pollution.

Any wet processing of coffee produces coffee wastewater which can be a pollutant. Ecologically sensitive farms reprocess the wastewater along with the shell and mucilage as compost to be used in soil fertilization programs. The amount of water used in processing can vary, but most often is used in a 1 to 1 ratio.

After the pulp has been removed what is left is the bean surrounded by two additional layers, the silver skin and the parchment. The beans must be dried to a water content of about 10% before they are stable. Coffee beans can be dried in the sun or by machine but in most cases it is dried in the sun to 12-13% moisture and brought down to 10% by machine. Drying entirely by machine is normally only done where space is at a premium or the humidity is too high for the beans to dry before mildewing.

When dried in the sun coffee is most often spread out in rows on large patios where it needs to be raked every six hours to promote even drying and prevent the growth of mildew. Some coffee is dried on large raised tables where the coffee is turned by hand. Drying coffee this way has the advantage of allowing air to circulate better around the beans promoting more even drying but increases cost and labor significantly.

After the drying process (in the sun or through machines), the parchment skin or pergamino is thoroughly dry and crumbly, and easily removed in the hulling process. Coffee occasionally is sold and shipped in parchment or en pergamino, but most often a machine called a huller is used to crunch off the parchment skin before the beans are shipped.

Saludos Steve.

Keep the good times rolling !!!